While other events may have left much to be desired, 2017 was a goldmine for movies. Several countries produced a slew of important films. Masterpieces like “Get Out” and “Three Bilboards Outside of Edding, Missoura” from the US; “Hobbyhorse Revolution” from Finland; and “Strawberry Days” from Sweden. There were wondrous, deep, dark, and diverse stories told by the cinematic artists of the time. Stories about underpaid workers, and documentaries that explored girlhood through unusual hobbies.

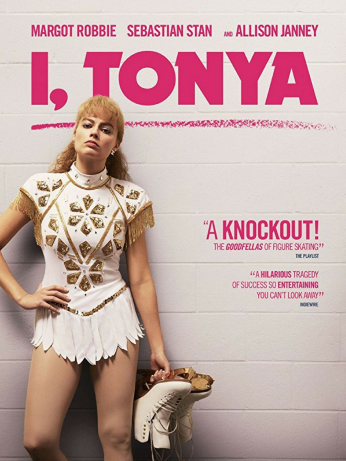

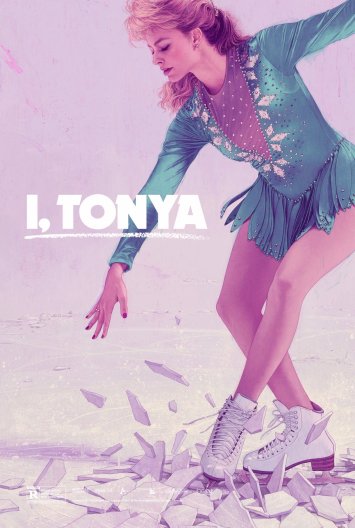

Especially class and morally grey characters became a major subject in American cinema of the time, showcasing situations that lacked a clear right or wrong scenario. One of the most noticeable examples of this kind of film was the experimental biopic “I, Tonya”, directed by Craig Gillespie and starring Margot Robbie. It tells a Rashomon-style tale of the infamous figure skating star Tonya Harding. Harding was known for two things. The first is that she was the first American woman to land the difficult and sublime triple axel in US Championships. The second, however in contradistinction to this axel achievement, was the brutal attack her husband Jeff carried out on fellow athlete Nancy Kerrigan in 1991. The first, assuredly a wild accomplishment to the skating career of Ms Harding; the second a devious action that still has a obscuring shadow lingering over it, shrouding the extent of Hardings involvement. To this date the degree of participation is still wildly speculated upon and runs the gamut of total to no involvement whatsoever.

While “I, Tonya” has been marketed as a biopic, the film offers a lot more than a fall from grace celebrity tale. It is also a story that deconstructs the idea of a self-made person, detailing the spirals of domestic abuse and showcasing the complexities of truth. In fact, when this blogger had left the theatre with her friend and we were discussing it, the friend in question stated: “If anything, this film depicts that there is no bigger tragedy than that of a child who was not loved”.

“I, Tonya” opens by setting up the mock-documentary (mocumentary) like style, with a unseen camera crew interviewing Tonya, her ex-husband Jeff, her mother Lavona and her ex-coach Diane, all sitting down to recap Tonya’s life, leading up to “the incident”. The audience is introduced to the early girlhood of Tonya. Her childhood was imprinted through growing up lower class and marked by intense physical abused (almost daily, it seems) committed by her mother Lavona. In one particularly heartbreaking scene of her childhood, the young Tonya remembers being abandoned by her father, who she has seen as someone who she could turn to in troubled times. Despite her desperate pleas, her father eventually disappears, divorcing Lavona and leaving Tonya abandoned to the mercy of her abuser. The filmic narrative of Tonya’s childhood is the beginning development of a person created in the grasp of hopelessness and resentment.

Tonya’s adolescence and early youth forces her to a deeper alienation as her days are continuously marred with classist mocking from her peers, both at her school and at her skating lessons. Tonya mentions, between these childhood filmic flashbacks, that she has always consider herself, and been open about the stance of, “being a redneck”. This declaration is both an ironic echo of the dual shame and pride of her lower-class origins, as well as a implementation of the harsh narrative arch forming the later tale of Tonya.

When Tonya becomes a teen, she meets her future husband Jeff. They bond almost immediately. In one particularly telling scene, Tonya and Jeff meet up and Tonya talks about her fur-coat, saying: “I bought this recently, my family has money – my stepdad was unemployed for a while but now we have money”. Jeff replies with a simple, matter-of-fact “My family is poor”, which brings a smile to Tonya’s face. Tonya is used to having to hide her poverty, so much that she tiptoes around the fact when speaking with Jeff. When Jeff, whom Tonya is attracted to, openly speaks of being poor, this gives a clear comfort to Tonya. The smile that we the audience see on her face shows us that Jeff is one of the first people to give Tonya the sense that she doesn’t have to face a stigma for her upbringing. This hope is later crushed when the abuse begins, now at the hands of a new loved one, Jeff.

“I, Tonya”’s narrative structure delves into a number of possible scenarios in the manifestations of Jeff and Tonya’s relationship. Jeff in the interviews claims he was not abusive, and that it was Tonya who abused him. Tonya claims that Jeff hit her almost from the start of their relationship. The third option, haunting this interchange, and one the audience sees with a subtle third eye of the film, is that both were abusive towards one another. Lingering over this interaction the film effectually connects the violence Tonya experiences at her mother’s hands and the violence between Tonya and Jeff. In the mid-section of this montage we see a Jeff abusing Tonya followed unsettlingly with them immediately having sex. This filmic section breaks when the younger Tonya turns her head to the camera and states: “My mum hits me and she loves me, so it must be the same with Jeff, right?”. The destructive, horrid link of Abuse and Love is continued when Lavona berates Tonya for staying with Jeff despite the obvious bruises, to which Tonya states: “Well, where must I have gotten the idea that hitting is ok from then, huh?”. As all interchanges between the mother and daughter this tense conversation leads to Lavona hurling a knife into Tonya’s arm (a scene so shocking that the audience gasped in horror).

Lavona

Tonya ensnared in a (potentially mutual) abusive relationship is narratively linked to her abusive childhood. Circling continually in the warp connection of love and abuse, Tonya has learned to normalize violence as well as her resentment and bitterness steaming from Lavona’s mistreatment. Oppression begins at home where the anger and violence are justified in toxic affection. What sad events were to unfold already found ground in Tonya’s house, community and life.

While skating gives Tonya a sense of purpose, it also is a place of great conflict; from early on, despite her performances being impressive, the judges give her lower scores due to her costumes that are, as the film shows, homemade. Tonya, due to not being able to afford the outfits expected of a skater, is furiously frustrated at the disadvantage her class gives her, and, when finally finding the voice to confront a judge about this injustice, pleads “can’t it just be about the skating?”. The fact that Tonya financially struggles as well as having a non-nuclear (or healthy) family is a burden which is not easily carried and is socially realized in the skating community when one judge admits to her low-scoring being a function of her class and not “having a wholesome American family”. The filmic narrative looks deep into the realities of class and deconstructs a very old idea of the self-made person and the American dream.

A Furious Tonya

Being from an abusive family, and revolving continually about those whose love is professed in the ambiguous intents of violence, it is not strange that we experience a Tonya that lingers in the fields of anger. The film shows a Tonya often unable to cope with her temper. These bouts of fury devolve quickly becoming often unpleasant and uncontrolled. These elongated episodes of rage combined with the stigma of “white trash” attached to a kitschy costumed Tonya creates a valley of unfair treatment by the judges to which Tonya is not able to emerge from.

Often, in the style of holding up the idea of the American dream, the rags to riches trope overlooks the fact that being poor is, as Chris Kraus stated in “I Love Dick”, more than just the physical experience of lacking basic things, but also a mental experience – one that can leave actual psychological wounds. People that are able to escape and survive poverty have to still deal with the painful memories; for example people who have gone hungry will develop “quirks” later on in life, due to the fear of experiencing hunger again. In stories of people moving from one class to another, the psychological complications are often ignored. To further complicate things, classist behavior also exhibits itself in different ways in our society. “I, Tonya” avoids these problematics and explores an honest depiction of class and surviving poverty without sugar-coating. The journey of moving from lower class to the field of a sport founded on the upper residues of society creates a plethora of problems, hesitations and even scars. It is far from the clear-cut move and simplistic revision, from lower to upper as our society naively states. Tonya’s navigates a complex set of emotions and social emotions in regard to her. She deals with the insecurities and stigma of being poor, and the scars and traps of a dysfuntional family (another aspect where people judge the poor more harshly than other classes). A new narrative towards the poor is necessary. One that shows the actual horrific struggles, imprinting of the deadly experience of poverty, and the harsh insecurities caused in great lack. This new narrative is springing forth and is essential to the grand understandings of all classes within our social systems. “I, Tonya”, doesn’t shy away from this new, uncomfortable and frank narrative.

Beyond the themes of class and abuse, “I, Tonya” has a great cast and uses the trope of the unreliable narrator excellently. The narrative progression of the film plays with the audiences expectations, granting the viewer space for their own interpretations, and opening speculation of how things may have truly have been. The uncertain is the progressive gear in the films structure and, in regards to the incident of the violent attack on another skater, the viewer is left unbound in knowing how much did Tonya and what understandings she had?

The film yields up a Tonya who is hot blooded and prone to anger, but is still a compelling anti-hero or anti-villain (depending on your interpretation). The characters are often unlikeable, but complex. The film is also visually stunning. When Tonya is first seen skating in competition, it feels like you’re on the ice with her. Moving, dynamic, uncertain, the film gives a ambiguous narrative of truth and a stunning visual of movement.

“I, Tonya” is a remarkable triumph: a movie about a controversial, upsetting subject that ends up saying much more than one would expect. It is definitely a film worth seeing in every sense of the word.

“I Am Not A Witch”: Review!

“I Am Not A Witch” (2017) is a Zambian film that mixes magic realism with biting social commentary. For those interested in dipping their toes into African Cinema, I highly recommend!

With Love/ Maaretta