It´s International Woman´s day! Usually for this day I would do a list of articles concerning Women´s rights and liberations across the world, but this year comes a decision to change things up a bit. Instead I will list a few feminist books and stories that are more than worth checking out. In order to explain what, in this list, is meant by a feminist read I´ll make a short explanation: it is a story that has three dimensional female characters and either deals with the subject of female liberation or deals with the subject of female oppression. Let´s get started.

Quick Note!: Most of these books can be triggering due to dealing with rape and violence.

1.“Changes: A love story” by Ama Ata Aidoo: This is a classic work of African literature, and for no small reason. The book takes place in the 1990´s Accra, Ghana, where the independent Esi decides to divorce her husband due to having endured a rape at his hands. After that she falls in love with a Muslim man named Ali, which leads her to question whether or not she should become his second wife. “Changes” was published in 1993 and was one of the first African books that dealt with women trying to balance home life with work as well as the stigma of being an independent woman. But it also openly deals with marital rape and its aftermath, which even to this day is still a taboo subject in much of literature and culture (including western). Esi´s struggles against expectations are shown in a complex light; while she is determined to keep her job and independence she finds herself still inclined to forgo her autonomy to please Ali and others. The book is honest and human. As the saying goes, the personal is highly political, especially for Esi.

2.“Purge” by Sofi Oksanen; This novel takes place in both modern times free Estonia and the Estonia of WWII, when it was under Russian occupation. The story is about an old woman meeting a young woman; Aliide Truu, a woman who was rape and sexually tortured by KGB agents in her youth, and Oksana – a youth who has escaped from the hands of traffickers. Oksanen delves deftly, but horrifically, into a story of two forms of sexual violence; that of politically motivated rape and that of modern day sexual slavery. The novel is heavily disturbing, but the characters, especially Aliide, are wonderfully complex and the illustration of female oppression is powerfully exposed. It´s best to not say too much, since the plot´s enigmatic structure makes it a book best to read blindly.

3.”The Ribbon Maiden”: This fairy tale, which originates from the Chinese ethnic minority of the Miao, is about a woman who people proclaim as the maker and creator of the most beautiful sowing and ribbons found in the land. The emperor, wanting this skill only to himself, has The ribbon maiden kidnapped and held against her will unless she makes him a continuous supply of the elegant ribbons. She submits to the emperors demands, but due to her great talents she is able to make the emperors bondage of her backfire on him. The tale is laden with female power – from the Ribbon Maidens wish to return home so she can reunite with her female friends, to her refusing to submit to the bully emperor. It is impossible not to cheer on this woman as her many gifts, and powerful sowing, defeats her captors and manifests her freedom in the face of oppressions both political and ideological. A really, really cool fairy tale.

Miao woman wearing traditional clothing

4.“Blood and Guts in High School” by Kathy Acker: The most absurd and weird novel on this list tells the story of a woman who endures emotional abuse, trafficking and abandonment. The writing is surrealistic and the story is told in a nonsensical order, with Ms. Acker´s own NSFW yet creative drawings. The prose is a surging gush of rage and aggression, delivering a punk-themed punch to the capitalist patriarchy. Beautifully random.

page from “Blood and Guts in high school”

5. “Ladies Coupé” by Anita Nair: This book is formed of an assorted set of narratives focused on diverse women of Today´s India. A woman aboard a train contemplates if she should run off with a younger man she´s in love with or stay with her conservative family instead. Finding herself in the company of a group of women during her trip she asks for advice. What follows are a myriad of tales of life and struggle – the serene joy of learning to swim, of getting the last wondrous laugh against a bully husband, and the lonely tragedy of being impregnated via rape. The tone continuously pivots from the lighthearted to the cruel throughout the entirety of the narrative, with both the epic and minute of characterizations. Despite some stories being tragic, the novel leaves a clear hope in the end, depicting a happier life just around the corner.

6.“From a crooked rib” by Nuruddin Farah: This novel takes place in 1980´s Somalia, where a nineteen year old girl runs away from home to escape an arrange marriage, only to find herself having to marry other, equally unpleasant men, in order to survive. Beyond all hope, and needing both men to ensure her social and monetary survival, she navigates a precipice to keep secret her twin marriages from both men (she hasn´t legally divorced either one of them). Farah illustrates the economic and political challenges facing women in Somalia and minutely exposes how the social mores, and legal system is biased against women (and laying bare double standards applied to men, as opposed to women, when it comes to marriage and relationships). While the heroines husbands both indulge openly and continuously in second wives and many lovers, the protagonist finds herself mercilessly slut-shamed, tormented and ostracized by the community for falling outside of the hallow prescripts of monogamy. “From a crooked rib” was Farah´s debut novel, but you would never guess that.

7.“The Butcher´s Wife” by Li Ang: Based on real events, this story is about a Taiwanese woman, Lin Shi, who after taking years of absolutely ruthless abuse kills her husband in self defense. The story begins when the protagonist’s parents, fearing Lin Shi’s youthful behavior as signs of uncontrollable and uncontainable sexuality, marry her off to a local butcher, who it turns out is fond of making Lin Shi scream in agony. He abuses her both physically and sexually, and when she starts to defend herself he starves her. One of the toughest books I´ve ever read, but none the less this novel remains gripping and spellbinding. The novel not only showcases abuse, but critiques neighbors and family members that enable abuse through ignorance and acceptance, as well as showing a side of the local Buddhist religion which is not a flattering depiction to say the least. Thought-provoking yet brutal.

8.“The House on Mango Street” by Sandra Cisneros: The story of a Mexican-American family is told in a series of drabbles in this short book. Through the narration of the adolescent Esperanza these petite deft drabbles explore poverty, culture, sexual assault and hope. The stories are like extended poems, with heartbreaking scene after heartbreaking scene. From Esperanza witnessing her father grief stricken by her grandmother’s death to Esperanza being sexually attacked by racist white boys, the novel makes a depressing, memorable quick read.

9.“The House of Bernarda Alba” by Federico Garcia Lorca: This was not only an unusual play for it´s time for its open brutal criticism of Spanish honor culture, but is also remarkable by even today´s standards in being a play with a all female cast with no speaking roles for men, as well as dealing with female sexual frustration. The play is about a classist, narrow minded mother who rules over her five daughters with an Iron fist, never allowing them to socialize with others in the town or marry. This leads to a major conflict when a young man arrives and three of the same sisters are smitten with him. Things become especially disturbing when the youngest daughter is implied to be pregnant without being engaged. The sisters play off each other perfectly, and the deep seated melancholy and sense of being trapped in being an “honorable woman” echoes through the story with great strength.

10. “Woman at Point Zero” by Nawal El-Sadaawi: the angriest and fiercest work in this list by fair, El-Sadaawi´s classic novel tells the story of a woman on death row that has killed her pimp. The woman details her life from girlhood to the point where she ended up in prison, describing her ordeal with female genital mutilation, male betrayal and violence. Through the course of the novel the protagonist makes abundantly clear how she has come to be so angry and uncompromising with the world she lives in, where, beginning with her birth as a woman, she was set up for pain. The woman´s narration bursts with a fire at the face and fact of an unjust world. It is provocative and unapologetic, an instant masterpiece.

Ms. Nawal El-Sadaawi

That´s a few recommendations. What feminist novels, short stories/ fairy tales or graphic novels do you readers recommend? Comment done below and A Happy International Women´s Day to all sisters, Cis to Trans, out there!

Short Story Review: Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie´s “Cell One” Explores Class Priviledge, Empathy And Ill-Treatment Of Prisoners

(Trigger warning for discussions of poor prison conditions and torture)

It is probable Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie does not need an introduction. She´s the writer everybody reads, she tops all the best seller list, and she´s well loved by book lovers of the world. Her most famous work, “Half of a Yellow Sun”, has been adapted into a film. Her books have won numerous awards and to many, she´s an introduction to African Literature. Gushing about “Americanah” or “Half of a Yellow Sun” is expected from everyone. While indeed her novels are masterpieces, very few people have actually talked about her short story collection, “The Thing around your neck”. It is a shame, because in her stories she deals with many important issues such as sexism, racism, homophobia and colonization. Her short story collection is diverse not only by including many LGBT-characters and having a cast full of POCs, but also in different story settings. She has a historical story, stories about rich people, stories about poor people, a story about writers, stories of politics. The narration also differs in tone in many stories. And while perhaps not all the stories are great, they all capture a certain truth about ordinary lives.

Ms. Adichie

“Cell One” is narrated by a young girl, who is in fact not the real protagonist of the story. Her narration is done by casting a cynical, fed-up eye on her rowdy and small criminal big brother, Nnanamadia, and her parents who continually enable his behavior. The family is fairly wealthy and the brother in fact is heavily implied to continually even steal from his own family. His criminal behavior comes from his involvement with gangs at his university, which early in the story leads him into being imprisoned. This comes as a terrible blow to the parents, but the narrator sees this as her brother getting his just deserts. While it´s never explicably stated, this resentment most certainly comes from parental favoritism and a sense of the brother using his male privilege to get his parents to let him get away with terrible behavior. This dynamic reminded me of Jamaica Kincaid’s memoir, “My brother”, where Ms. Kincaid discussed parental favoritism combined with gendered double standards: her mother would allow her brother to be a slacker while being quite tough on her daughter. While the parents are not harsh towards the girl in this story, she on the other hand has become resentful of her brother.

The plot revolves around the family´s visits to the prison. Nnanamadia first is haughty, but slowly he starts to change over the course of the visits. He starts mentioning an old man who has also been brought to the same prison. This man has been arrested since the police couldn´t find his criminal son, and therefore imprisoned him instead despite a lack of evidence he had broken any laws, and to add insult to injury they also threat him with less respect due to him being poor.

All four of Ms. Adichie´s books covers in Finnish

As time passes on, Nnanamadia begins to mention and talk about the old man whenever the family visits him. He becomes more and more melancholy in his speech, talking about how the guards are nasty and mean-spirited towards a fragile man who´s harmless. He talks about how no one visits the man, and how the guards neglect the old man in favor of other prisoners. Through the dialogue, the reader begins to notice a huge change in Nnamanadia; before he was conniving and self-centered, but after his witnessing of the fate of the old man, he has begun a venture of human maturation into an empathetic person who sees outside of his own world. With every visit he goes further into his metamorphosis. A particular telling moment is when the parents bring food for Nnamanadia during their visit. Nnanamadia looks at the food, and quietly states that he wants to give it to the old man, who is not properly fed in the prison. The guards blandly and blankly state that this is not allowed; Nnanamadia just silently stares at this offering of food from the family torn and distrait at the inhumanities brought up in the gift. He´s attachment to the old man makes him want to for the first time in his life prioritize someone else besides himself.

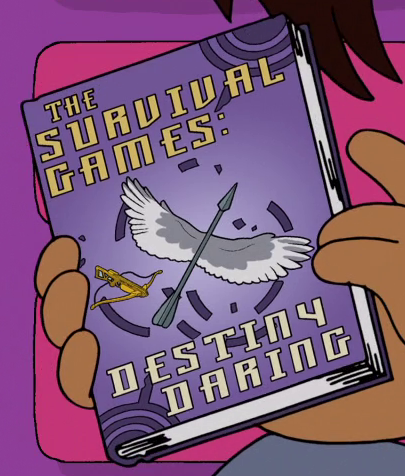

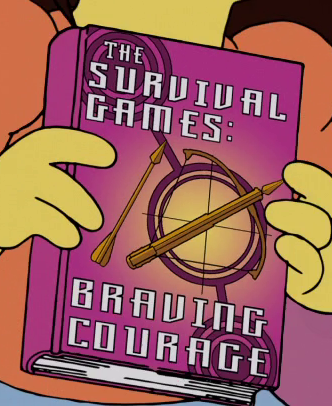

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie´s works were even referenced in “The Simpsons”

In the climax of the story, Nnanamadia is taken into cell one, where he is severely beaten as a form of torture. And frankly, when the guards tell the parents why this horror is visited on Nnanamadia it becomes as intellectually appalling as emotionally wrenching experience for the reader.

Drawing from The New Yorker in these publication of this story

What makes “Cell one” such an incredibly story is that it packs many social and political issues such as corruption, harsh prison conditions and class into a narrative lodged acutely in the intimate and personal. The issues are deeply tied with the character growth of Nnanamadia and his tale of growing understanding casts the reader into an optimistic stance of the possible and hopeful side of human behavior. It is contrasted by the guard’s cruelty, which makes them a great foil to Nnanamadia. There´s an old saying in the feminist movement, “The personal is political”, which this story captures by showing how politics and corruption affect the old man’s life as well as Nnanamadia´s coming of age. By showing how the machinations of corruption detours, deforms and defeats human lives – and it is the most fundamental aspects of human existence that are at stake in these questions – Adichie´s writing is an ideal example of social commentary done with concerned focus and sure precision.

Cover for “The thing around your neck” in Swedish

“Cell one” is a breathtaking tale, and despite not being a novel, has all the great elements of a literary magnum opus. It would, in my opinion, be also amazing to see this story adapted into a film. The prose is perfect, even in the advents of the young girl’s resentment, and the wondrous personal honesty of the voice of the narration flings the reader along an engrossing plot filled with heartbreaking events. This is political fiction at largest and finest.