(Trigger Warning for discussions of Torture)

This is the first post for “Torture Awareness Month”

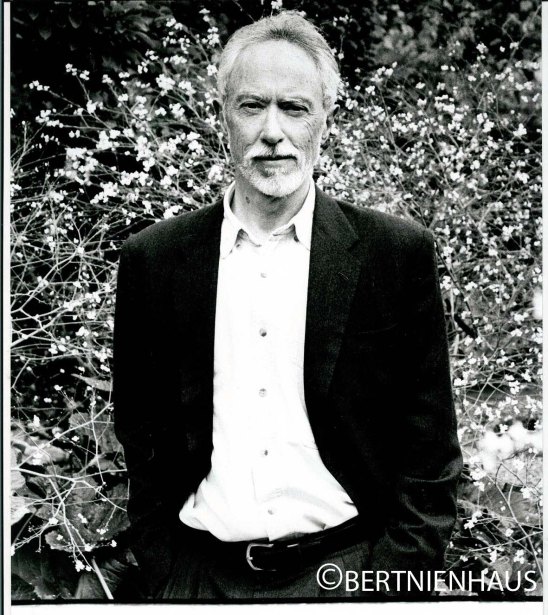

J. M. Coetzee is a South African novelist who won the Nobel Prize in 2003 and was the first person to win the Man Booker Price twice. His most famous novels include “Disgrace”, “Life and Times of Michael K” and “In the Heart of the Country”. His works often deal with corruption, racial tensions, and violence. The work for which he is most well known lies probably with “Disgrace”, which a large swath of critics have praised for its complex depictions of a post-apartheid South Africa. However this is overlooking a slim volume, which one can maintain is Mr. Coetzee´s Magnum Opus, the insightful and unsettling “Waiting for the Barbarians” (published in 1980).

“Waiting for the Barbarians” tells a story of a Magistrate (he is never given a name outside of his title), who witnesses his community as it is torn apart and pieced together upside down by the arrival of a new malicious colonel. This new colonel has arrived to investigate the assumed threat of “the barbarians” who will/may invade the small haven. The Magistrate explains that the people in his village have all admitted to fearing the barbarians; afraid that they will come in the middle of a night, rape their daughters and set fire to their houses. The new colonel tortures a young boy with a knife, who due to the torture claims he knows of a group that was planning an attack. After the random interrogation the Magistrate is allowed to speak with the boy, whose body is maimed and crisscrossed with cuts. The magistrate is told that the boy was tortured with a knife (“a very small knife”, the guard claims) and the Magistrate asks the boy if he knows the full consequences of his “confession”, but the boy is understandably too frightened to answer. Whereupon a witch-hunt begins that leads to mass arrests, legal abuses and mass torture of the people of the community now under control and intimidation of the new colonel. The Magistrate tries to put a stop to the mistreatment of the people who are arrested, but never tried with actual crimes, which only leads to his imprisonment under the new regime justified in their fears of the coming Barbarians.

These “fears” of the novel, convicted by those in power and foisted onto the populace, notably are the fears that historically have been used in propaganda to demonize the other for many a century and over many a land. “The other”, many times, may it be a different race, religious group or nation, has been posited as a threat to the sanity of members world and worldview. The Other is out too hurt and destroy “us” in these clichéd manners such as “set fire to our houses” or “rape our women”. (These demonizations also helped to cover up when people inside a certain group commits atrocities, for example the myth of black men raping white women in the US helped many white men to get away with rape, while killing many falsely accused black men). In short, it is well known that every nation has at some time feared those fears which the Magistrate describes in the content of the novel.

In “Waiting for the Barbarians” the country or people the story tells about are never specified. Indeed the book seems to not be about any real country, but a completely fictional one. There are no dates and the years in which the events take place are absent. Furthermore, the identity of the barbarians whom people fear and the cause of the panic are never explained. These elements are what make “Waiting for The Barbarians” a masterpiece that it is, since it exposes a fundamental truth about humans and morality: that fear, if misguided, will create opportunities for powerful men to get away with grand injustices. Many critics saw parallels to the Apartheid in “Waiting for the Barbarians”; some other saw parallels to American politics post 9/11. Such scenarios which are displayed in “Waiting For the Barbarians” have unfortunately happened repeatedly and to this day people are still being tortured and killed due to the inclinations of such hateful propaganda and the vague ideologies which motivate fears of the “outside”. The message from “Waiting for the Barbarians” is important and sadly still relevant.

While The Magistrate is the narrator, the novel still provides point of views from the people accused of being, or being “in league” with, the barbarians. One of the most memorable examples is a woman the Magistrate rescues from begging. She is nearly blind after an incident which occurred when she and her father were suspected, without any proof, of being threats. Her father was beaten. To make him feel powerless, hot iron was nearly put against the woman’s eyes; while not burning her, it severely damaged her eye-sight. The interrogators/torturers had held the iron near her eyes for a while, threatening her father that they would blind her. The Magistrate even comments that he can even see that her eyes do not resemble common eyes. The girl explains that her father became very quiet and didn’t move much after this incident during his torture and afterwards he just stared down at the floor avoiding any and all eye contact with her. He later died, leaving her by herself. She soon after found herself tossed into the streets now being seen as tainted by the mark of the Other. The Magistrate later elaborates on this incident. He suggests that the reason that the father died was that he could not stand the fact that he had failed to protect his daughter. The Magistrate puts himself in the father’s position, and concludes that such a situation was so horrid, the idea of having to just watch as one’s child is being tortured and being helpless to do anything is such a nightmare, that it is “no wonder he wanted to die”.

According to the Swedish section of the Red Cross (who, among other things, specialize in rehabilitation of torture survivors and spreading awareness about mistreatment of civilians) this form of torture, hurting someone else to make the other one feel shame and fear, is found to be a largely typical form of torture. At times it’s a friend or a family member that is threatened harm, or actually hurt in front of the actual focus of the torture. While the girl in “Waiting for the Barbarians” is not a minor, the idea of one’s child being tortured is unfortunately not as unlikely as one could wish. According to one of the studies made by Amnesty International, children have been flogged in secret Syrian prisons. Torture of children has also occurred in Turkey (around the early 2000), as well as in Bahrain. Coetzee in this scene not only illustrates a realistic torture scene, but also invokes an important emotion through the Magistrates narration: Empathy for the victim. When the girl tells her and her father’s story, the Magistrate feels the pain in her memories. That pain is so great that it kills her father. That injustice is so harsh that doesn’t end after the interrogation. It stays and affects the girl’s life even after she is let out of the prison.

The Magistrates empathy doesn’t end at the girl. When he gets to the main courts holding area, where the so-accused barbarians are kept, he witnesses a whipping. A child who is witnessing the public torture is asked to whip the prisoner in order that he can learn how to do so “correctly”. The Magistrate, reaching the limits of his own apathy, and runs up to stop the child become part of the horrid scenario as he knows that what is happening is that the child is being taught to not feel empathy, he is being taught to inflict pain without recognizing the prisoner as a fellow person. This corruption of the child, of planting a new generation of fearers and torturers, is too much.

The corrupt idea of torture is completely deconstructed in the novel “Waiting for the Barbarians”. There are few novels similar to it (if there are any novels like this at all). Not only is torture shown as a misguided way to get proper information (the young boy tortured at the novels beginning lies to put an end to his ill-treatment) but it also shows how anyone in the midst of aimless fears, empty empathy, and the discounting of the humanity of others, can become all too easily the dismissed of society and the subject of torture. “Waiting for the Barbarians” makes the reader feel the pain that the victims go through, makes the reader feel empathy for those who have been stripped of their humanity and being in torture, and bares the ideological corruption which motivates individuals and societies to embrace the sightless horror of torture. This delving into the aspects of disenfranchisement and torture, both social and as individual, is essential for us to confront as often in media news torture is separated strongly from the viewer making the torture actions seem only to be “enhanced interrogation”, or in fiction media which uses torture mainly for a prop device as a way to add excitement and to keep audience’s attention (and which also separates the viewer from the actualities of torture, see Especially American televisions 24, Warehouse 13, Homeland to name a few).

In this novel Mr. Coetzee demonstrates what torture actually is: it is the degradation of a human being, either causing death or at any rate causing lifelong emotional and physical scars.

“Waiting for the Barbarians” is bold in its call for empathy and humanization of torture survivors/victims. It is a challenge to see the diseased mentality of hate, and what such mentality can lead to. In its use of the imaginary lands it creates a truly universal story. For anyone who is interested in reading a more humanizing, realistic and ultimately compassionate look at people who are subjected to torture, this book is will not disappoint.

I think homeless people in Divergent myabe suppose to be barbarians in that universe.

That’s a possibility 🙂 if so, they most certainly don’t need to be afraid of them anymore, since their all homeless and powerless. 😦

Nice blog and review of Coetzee’s novel. I wrote a review many years ago, too for my English professor…a little bit different from yours. I wrote it when I was 23 years-old. I recently posted it on my new website: http://joecanuck.wix.com/justice4chinese#!white-genocide-in-south-africa/c2q4

What a coincidence – I´m 23 years old now, which means we write a review of this book at the same age! Was your review for a bachelor or…? I will definately look at your review, once I´m done writing my exam 🙂 Thanks for commenting!